Throughout her 36-year career in the justice sector, Chief Justice Martha Koome has protected the rights of women and girls in Kenya. Now, as head of the country’s judiciary, she leads from the front in transforming Kenya’s court processes to enhance access to justice for women and vulnerable groups.

“After law school, I joined a firm as a junior associate. I was given the ‘lowly’ work – according to senior partners. They did not consider the representation of women economically viable because they were often unable to pay, and the cases took forever in court,” Koome describes. “When I started my own law firm, I continued to represent women and children. I realized how difficult it was for [these groups] to access justice. In fact, our previous constitution was discriminatory against women and other vulnerable groups, it gave differential treatment to women who could be governed by customary laws on personal matters.”

As a lawyer, Koome joined the Federation of Women Lawyers in Kenya (FIDA) during the 1990s and played an active role in developing Kenya’s 2010 Constitution – securing the rights of women and children in the process.

“We worked very hard at FIDA to get laws reformed. I feel we have some of the best laws in Africa when it comes to the protection and promotion of women’s and children’s rights. We’re still lagging in terms of implementation [but] we are only 10 years into our constitution and we’re on the right trajectory,” the Chief Justice explains. “I participated heavily in the drafting of these laws and policy on how to protect the population from sexual offences.”

Kenya’s e-Judiciary and GBV response

Following her appointment in 2021, the Chief Justice launched the Social Transformation through Access to Justice vision which has a special focus on protecting the rights of vulnerable groups:

“We are conscious about the feminization of poverty in our communities. Digital exclusion tends to follow the same socio-economic trends. The tendency is for women to be disproportionally affected by factors linked to digital exclusion – lack of ICT devices, lack of electricity, power or the ability to pay for data.” These barriers also undermine GBV survivors in accessing justice, something that is also a priority for the Chief Justice. Between 2021-2022, the judiciary installed ICT services in 10 of the 20 High Court Stations around the country, which enabled over 700 cases to continue virtually:

“We’re working to ensure that survivors of GBV can access justice through technology. We now have reporting systems which also track and preserve evidence digitally.” explains the Chief Justice. She continues, “this approach is survivor-centered. Virtual hearings also remove travelling long distances to come to court. Survivors can give their evidence electronically. Virtual participation also helps with witness protection and minimizes retraumatizing survivors as they avoid having to recount experiences in open court. Virtual courts are going to be the way going forward.”

Innovating access to justice

Alongside the digital space, the Chief Justice has ambitious plans to fix inequalities women face in access to justice using a multi-sectoral approach. In 2022, she established Kenya’s first specialized court to handle GBV cases but has ambitious plans to scale this initiative nationally:

“The biggest problem we have encountered is the time it takes for cases to be completed. No survivor wants to come to court for 5 years. They want to forget, adjust, and carry on with their lives. Therefore we need specialized courts that are trauma-informed in all of the country’s GBV hotspots. We must be aggressive on ensuring we establish specialized courts with the necessary technology to deal with these matters efficiently.”

In addition to GBV, the Chief Justice has recognized the interconnectedness of women’s economic agency when it comes to inequality. “Targeting commercial activities that enable women to empower themselves economically is another priority as these issues are interlinked. Small claims courts are another necessary pathway to promote access to justice in trade and commerce. Women are often those with small businesses. We want to establish 100 small claims courts, if we can get those 100 courts operating it would really make a difference.”

Technology’s insidious side

While Kenya’s judiciary embraces technology to better serve GBV survivors, online violence is becoming a prominent form of GBV which is notoriously hard to report, investigate and prosecute. UN Women data estimates that 28% of women in Africa have experienced online violence in some form, with women in public life, journalists, and human rights defenders at greater risk. Online violence is an unsolved challenge globally, but Chief Justice Koome feels that concerted action, can – and must – be taken:

“The crime scene is extending to our computers and devices, and it is harder to reach. But this matter must be taken seriously. Survivors are traumatized and, in extreme cases, are committing suicide. Social media platforms must take responsibility for their platforms when they allow perpetrators to cause so much suffering. They have the ability to create such platforms, then they must take the responsibility to manage them properly and protect users. Society must also be able to stand up, and I don’t think we are doing enough.”

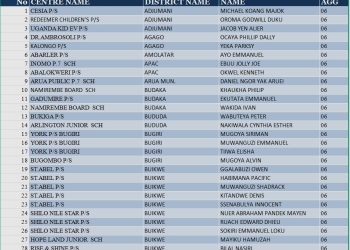

UN Women Kenya works with the judiciary to strengthen the capacity of justice actors through court user committees (CUCs) in Nairobi, Kisumu, Vihiga, and Bungoma counties. This initiative, supported by the Government of Italy, better equips survivors and duty-bearers with gender-responsive and survivor-centered approaches to reporting and managing cases of GBV.